Let’s Not get too Smug about Public Attitudes on Immigration

The text was originally published by the New Canadian Media. Click here to see the text with graphics or to watch the video of Professor banting delivering his speech.

Many international commentators have been impressed by the strength of public support for immigration in Canada. At a time of considerable backlash elsewhere, Canada has actually been increasing its annual immigration intake. When in late 2015 the federal government accepted 50,000 Syrian refugees, most commentators – Canadian and international – agreed that the secret to our comfort with immigration is a distinctive culture and identity that celebrates diversity.

And, yet, we also hear other voices in our immigration debates, voices that invoke cultural objections to immigration and multiculturalism. Moreover, we know that populist backlash elsewhere has been driven by a toxic combination of economic and cultural anxiety. We should be careful about assuming that support for immigration can be sustained on cultural grounds alone. We need to dig a little deeper.

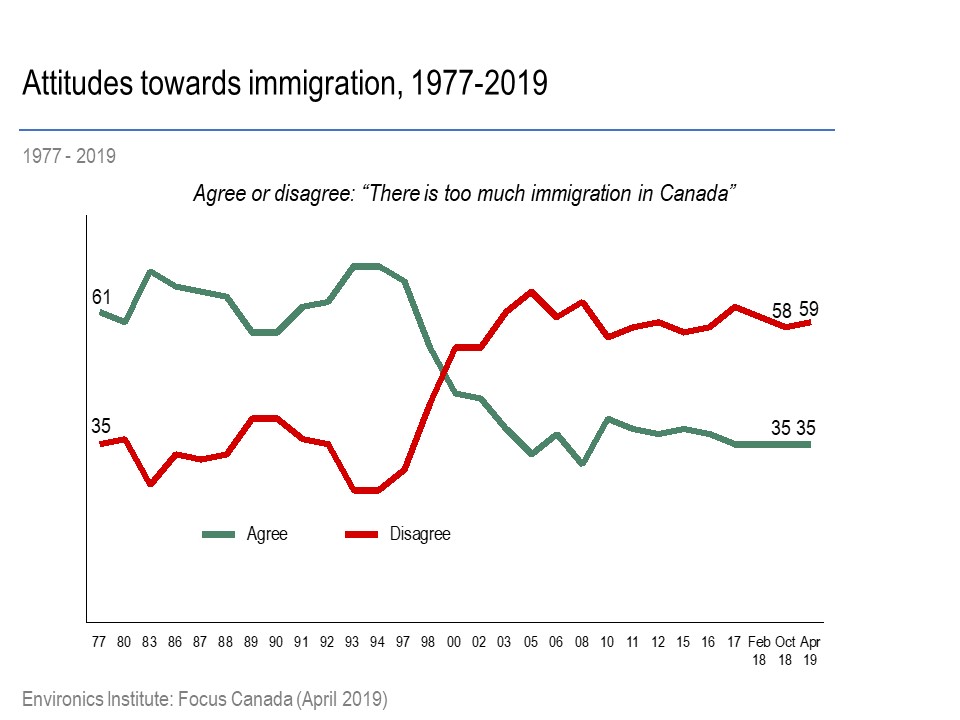

Canadians have not always been highly supportive of immigration. Historians have documented the many dark episodes in the first half of the 20th century, but we also need to pay attention to our more recent history. Until the mid-1990s, the overwhelming bulk of Canadians believed that immigration levels were too high. Then suddenly, in the middle of the decade, those public attitudes shifted dramatically. Support for immigration rose strongly, and by the early 2000s about 60% of Canadians supported existing immigration levels, support that has continued to be remarkably stable since.

Scapegoating Immigrants

I am old enough to remember when the unemployment rate hit 13% in the recession of the early 1980s and over 11% in the early 1990s. In those years, support for immigration rose and fell with the business cycle. But then the unemployment rate declined steadily as the 1990s progressed, reaching a much lower and relatively stable level after 2000 (in the 5% range at the moment). Moreover, the recession of 2007-08, which did such economic and political damage elsewhere, was reasonably short and comparatively mild here. This makes it harder to scapegoat immigrants, to complain they are stealing our jobs. The decline in the unemployment rate turns out to have been the strongest individual factor in our statistical analysis of the change in attitudes.

This economic impact was reinforced by the transformation of immigration into an economic program. Canada adopted the points system in 1967. But a points system doesn’t matter much if the economic class of immigrants is small. For decades after 1967, family reunification was by far the largest category. Once again, it was during the mid-1990s that the federal government dramatically squeezed family reunification and ramped up the economic class, making it by far the biggest category.

This is precisely the same period in which Canadians overwhelmingly came to believe that immigration is good for the economy.

‘Fitting In’

Multiculturalism plays an important role in softening internal boundaries in Canada. But culture plays a different role in who and how many get in the door. Cross-national surveys reveal that Canadians are as insistent as any European public that immigrants should ‘fit in’. In the current period, cultural anxieties about immigration seem especially prominent in Quebec, but cultural insecurity is hardly limited to that province.

The above figure reports responses to the proposition that “Too many immigrants are not adopting Canadian values.” There was some softening of Canadians cultural concern in the 2000s, but it bumped up again from roughly 2007 to 2015. Not surprisingly, in our analysis, the half of Canadians concerned about whether immigrants are adopting our values are clearly less likely to support ambitious immigration levels.

These cultural anxieties have undoubtedly contributed to – and have been reinforced – by increased political polarization over immigration in recent years. Surveys have shown that Conservative supporters differ in their views from those who lean in favour of other parties, helping explain how immigration is becoming more of an electoral issue.

However, so far, widespread belief that immigration is good for the economy seems to offset lingering cultural anxieties.

Looking Ahead

What does this tell us about the future? In 2016, the Advisory Council on Economic Growth to the Minister of Finance urged the federal government to raise immigration levels to 450,000 by 2021, an increase of 50% over the level at that time, as part of a strategy of growing the Canadian population. They argue that with other countries closing doors, this is Canada’s moment to move big. So far, the federal government has avoided such a bold commitment, but it has raised the target intake from roughly 270,000 in 2015 to a target of 350,000 in 2021.

There has been pushback, but not enough to fundamentally shift Canadian support. The continued decline in the unemployment rate into the 5% range might suggest we are on firm ground.

But a word of caution. We are in a curious period: the unemployment rate is no longer a good proxy for economic security. Despite such low unemployment, Canadians are uneasy – even anxious – about their economic prospects, and the economic future of their children. Growing inequality, disruption in the global economy, technological change, the gig economy and precarious forms of employment have generated a palpable sense of economic anxiety. Political parties are jockeying to tap into this unease in the current federal election campaign.

In my view, those who support Canada’s approach to immigration and who would like to see it grow – including me – should not assume support for immigration is simply baked into our culture. Supporters need to focus not just on instances of cultural intolerance, but also on issues of economic inequality, economic insecurity and social justice for Canadians generally, and especially the economically vulnerable. Limiting the potential for populist backlash requires working on both economic and cultural anxieties.

Keith Banting is Professor Emeritus in the Department of Political Studies at Queen’s University and a member of the Order of Canada. His research includes ethnic diversity, immigration and multiculturalism. This commentary is adapted from his recent Walrus Talks Boundaries at the Canadian Museum of History, Gatineau, QC, on Sept. 23.

Like what you're reading? With our bi-monthly e-newsletter, you can receive even more with the latest details on current projects, news, and events at the institute.

Subscribe