Having an election that changes nothing is not such a bad outcome after all

What, if anything, has changed?

Immediate media reaction to the federal election result is divided. Those who count the seats won and lost see the status quo. Those concerned with the tone and tenor of our politics fear the election has left the country more divided than ever. Is it possible that the election changed nothing and everything at the same time?

We can hardly be shocked that there are strong differences of opinion among Canadians—we wouldn’t need elections if there weren’t. Can we address climate change and increase oil and gas exports at the same time? Should we make child care more affordable by giving money to care providers or to consumers? Will subsidizing the cost of a mortgage make housing more or less affordable? Arguing over issues like these is not a threat to democracy; it is the point of democracy.

Canadians are divided, then, in the sense that we take different sides in these debates. But in another sense, we are not nearly as divided as many assume. Differences in opinion are scattered throughout the population, and do not separate us dramatically by region, or age, or gender, or race. There are oil-enthusiasts in Quebec and radical ecologists in Alberta. There are men who want $10-a-day national day care and women who would prefer to pocket a tax credit. There are new Canadians who trust the police and “old stock” Canadians who do not. We are not a country that is fracturing into increasingly hostile groups defined by geography or identity.

And only those with short historical memories can claim that our political divisions are greater than ever. Elections in the 1970s and 1980s featured heated exchanges over which party was going to save the country and which was going to put an end to it—whether by handing it over to the separatists or to the Americans. The National Energy Program was hardly less divisive than the carbon tax; Bill 101 was no less controversial than Bill 21. Canadians did not exactly rally together to embrace the introduction of the GST. Keith Spicer told us in June 1991 that the nation was riven by rage.

But all this is besides the point, if the real problem is the emergence of the People’s Party, and the associated rabble-rousers who yelled obscenities and threw rocks at the prime minister. Surely this is an indication of a society that is increasingly polarized?

Here, we need to be precise about the meaning of the words we use. Politics becomes polarized when more people move to opposing extremes, with far fewer remaining in the middle. This is what we see happening between Republicans and Democrats in the U.S., or between Leavers and Remainers in the U.K. There is no evidence that this is happening in Canada. Most Canadians remain firmly in the political centre, embracing the politics of pragmatic compromise and incremental progress.

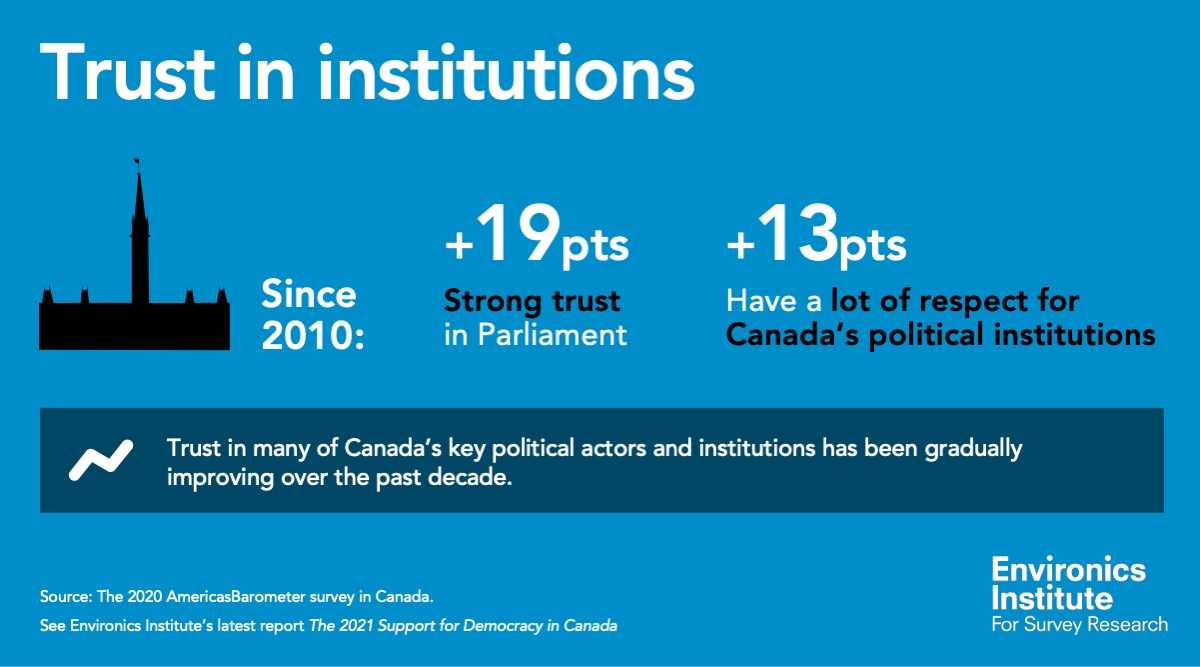

Some Canadians do hold extreme views, but the proportion who do so is not on the rise. Yes, it is sobering to consider that one in 10 Canadians agree that, under some circumstances, an authoritarian government may be preferable to a democratic one. But this proportion has hardly changed over the past decade—if anything, it is slightly lower in 2021 than it was in 2010. Meanwhile, the number of Canadians comfortable with the country’s diversity, and uncomfortable with racism and discrimination, is higher than ever.

While Canadians, as a whole, are not becoming more extremist, the extremists among us might be becoming more organized, and more empowered by social media. They may also be targets for further radicalization by those with the most sinister of political aims. This, and not widespread division or polarization, is the concern. The threat to our democracy does not come from the heated, even acrimonious debates between left and right, or East and West. But it may come from the small, but vocal minority that seeks to undermine the norms of democracy.

This threat should not be dismissed, but rather addressed swiftly by those knowledgeable in how to counter those seeking to infiltrate and radicalize. But this does not need to be accompanied by a generalized lament for the soul of a nation. The election may have been unnecessary; it may have been tedious and uninspired; it may have changed little as far as the composition of the House of Commons is concerned. But it did not leave us more polarized or divided than ever before. In that sense, having an election that changes nothing is not such a bad outcome after all.

Michael Adams is the founder and president of the Environics Institute for Survey Research. Andrew Parkin is the Environics Institute’s executive director.

Like what you're reading? With our bi-monthly e-newsletter, you can receive even more with the latest details on current projects, news, and events at the institute.

Subscribe