Experiences with COVID-19 and mental health

By Andrew Parkin (Environics Institute) and Justin Savoie (University of Toronto)

The COVID-19 pandemic had both immediate and lingering impacts on our health. The immediate ones were all too obvious: millions died or became seriously ill. While some recovered quickly, others experienced persistent symptoms for months, if not years. Combined with these physical effects was the toll the pandemic took on people’s mental health, as they faced loss and grief, exposure to new health risks, restrictions on regular activities, social isolation, economic strains and prolonged uncertainty.

The pandemic, as an official emergency, is technically over, though the virus continues to circulate. The various public health restrictions imposed in the first years of the pandemic have long since been lifted. Workplaces and schools have fully re-opened, travel for business and tourism has resumed, and sports and entertainment venues are eager to welcome as many spectators as they can. While some are still feeling the physical health impacts of COVID-19, most people have resumed their pre-pandemic lifestyles. Given this, is it reasonable to expect that the wider mental health effects have now faded as well?

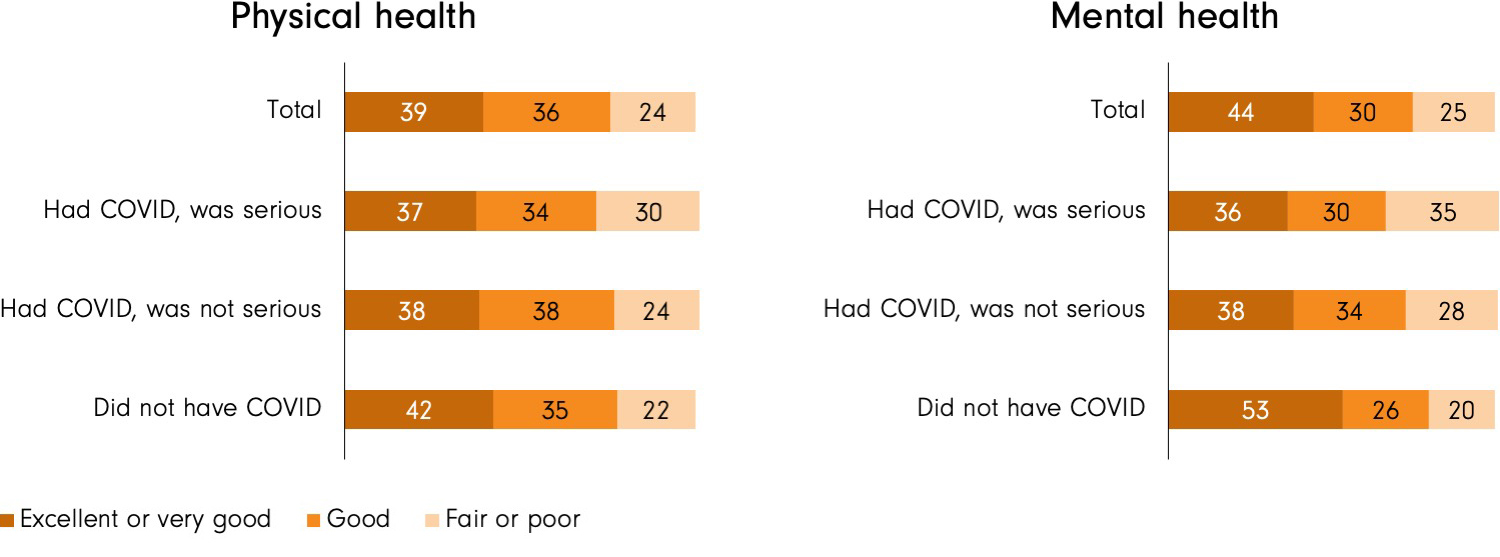

It appears that, despite the passage of time since the height of the pandemic, past experiences with COVID-19 may today be more likely to be associated with poor mental health than with poor physical health.

The results of several health-related questions from a recent Canadian survey suggests not. In fact, it appears that, despite the passage of time since the height of the pandemic, past experiences with COVID-19 may today be more likely to be associated with poor mental health than with poor physical health.

The survey, conducted early in 2024, asked 2,200 adult Canadians whether they had ever been sick with COVID-19 – and, if so, whether their illness was serious. Just over one in two (54%) said they had had COVID. (This is fewer than the actual proportion, as many are not aware that they were infected, especially if this occurred after vaccination.) Of these, 30 percent say their case was serious.

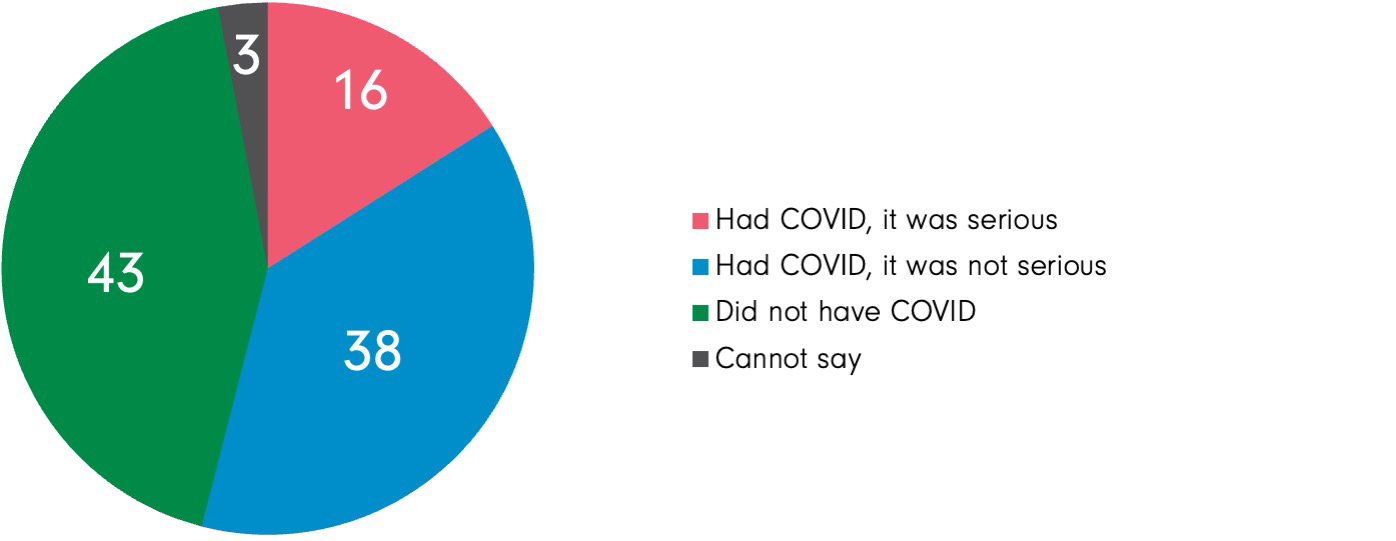

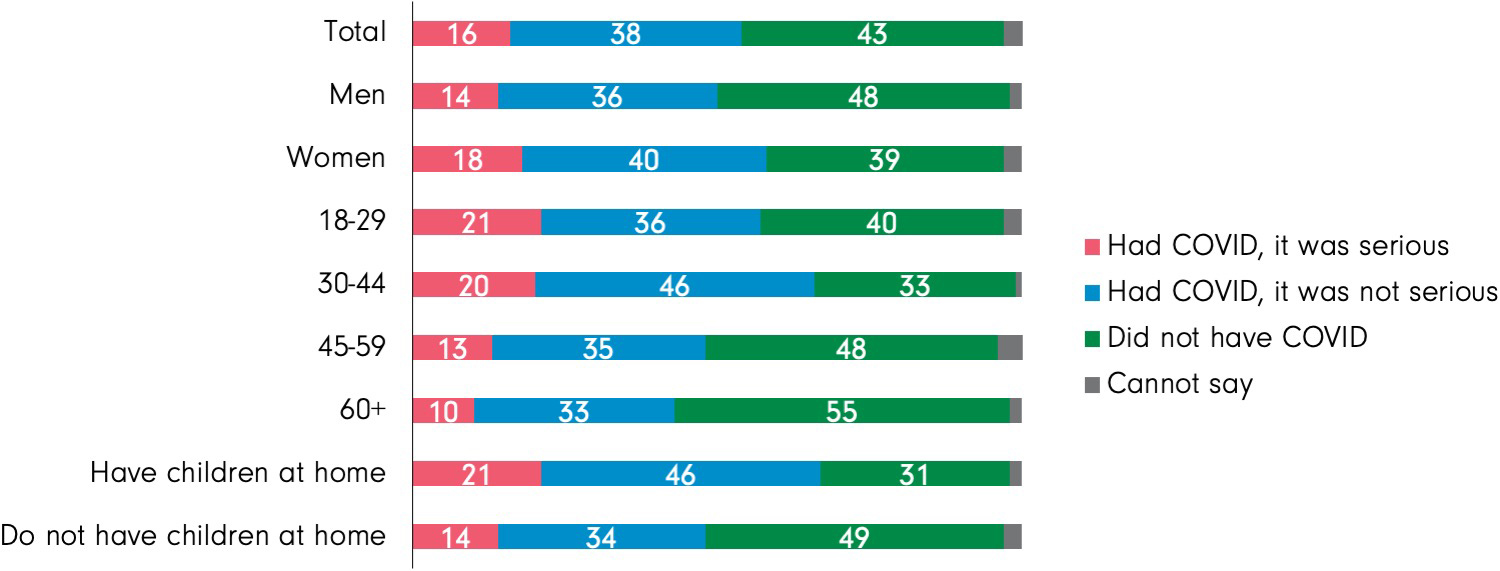

The total adult population thus divides as follows:

- 46% say they had not had COVID-19 (or say they don’t know);

- 38% say they had COVID-19, but it was not serious; and

- 16% say they had COVID-19 and it was serious.

Experiences with COVID-19

C6. Since the start of the pandemic in Canada in March 2020, have you ever been sick with COVID-19?

C7. How serious was your illness due to COVID-19?

What’s more, the difference between those reporting having had a serious case of COVID-19 and those who do not report having had it at all is greater when it comes to the incidence of poor mental health (a difference of 15 percentage points in the proportion reporting fair or poor mental health) than to the incidence of poor physical health (a difference of 8 points).

COVID and physical and mental health

C3. In general, would you say your physical health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?

C4. In general, would you say your mental health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?

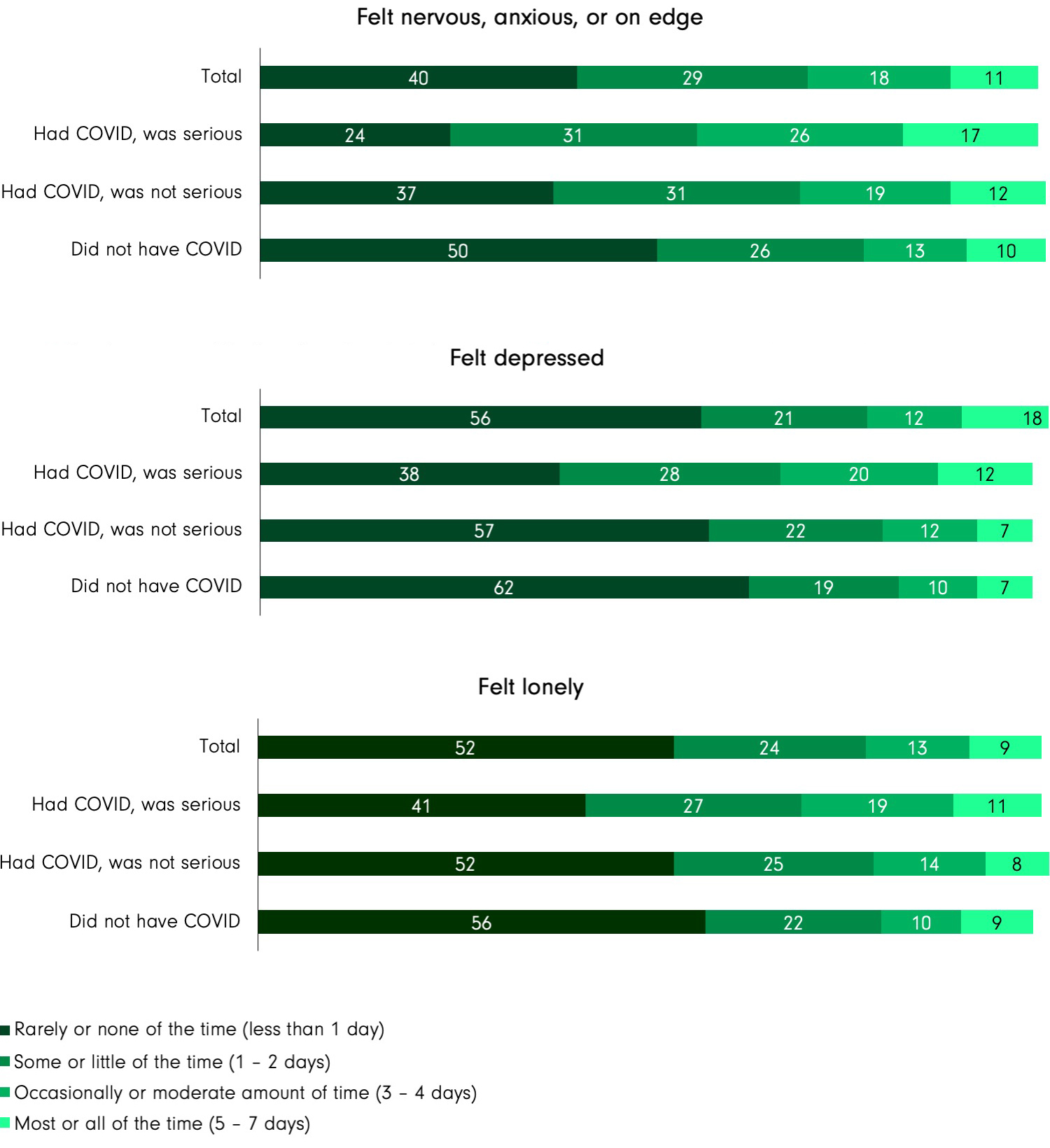

The same pattern holds when it comes to three other measures of well-being. The survey asked how frequently people might feel anxious, depressed or lonely. In each case, those who report having had a serious case of COVID-19 are much more likely to also report having had these feelings at least three days in the past week.

Specially, compared to those who do not report having had COVID-19 at all, those who say they had been seriously ill with COVID-19 are:

- 20 percentage points more likely to say they felt anxious at least three days in the past week (43%, compared to 23%);

- 15 percentage points more likely to say they felt depressed at least three days in the past week (32%, compared to 17%); and

- 11 percentage points more likely to say they felt lonely at least three days in the past week (30%, compared to 19%).

COVID and well-being

C5. In the past 7 days, how often have you experienced each of the following:

One is that people with poorer mental health were more likely to be seriously affected by COVID-19 (perhaps because their living or economic circumstances placed them at higher risk; or because they were less likely to have access to prompt medical care; or because their mental health was related to other pre-existing physical health conditions that also made them more vulnerable to the coronavirus).

Another is that people who have poorer mental health, or who are more anxious or depressed, assess their physical health situation differently (i.e., more negatively). In other words, they’re more likely to report having had COVID-19 and to describe their illness as serious.

Finally, as mentioned, it could be the case that – for some at least – being seriously ill with COVID-19 (or being ill with COVID-19 for an especially long period of time) has consequences for mental health and well-being that linger even after the physical illness has passed. Among other things, this could be because serious illness can be associated with greater social isolation and heightened economic insecurity.

These scenarios are not mutually exclusive.

Finally, these survey results are a reminder that many Canadians are affected by poor health in ways that may remain invisible to their family, friends and co-workers. People who appear physically well or who appear to have recovered from illness may be wrestling with other issues – including anxiety, depression and loneliness – that can’t be detected by a simple test you can pick up at the local pharmacy.

_________________________

Like what you're reading? With our bi-monthly e-newsletter, you can receive even more with the latest details on current projects, news, and events at the institute.

Subscribe