50 years of multiculturalism

The following article was published on October 7, 2021 by Canadian Geographic to mark the 50th anniversary of the announcement of multiculturalism as an official government policy.

50 years of multiculturalism: It’s as Canadian as maple syrup

Michael Adams, president of the Environics group of companies and the Environics Institute, and a regular contributor of published commentary on Canadian values and social trends, says most Canadians view multiculturalism as an important symbol of what we aspire to as a society

On Oct 8, 1971, then-Prime Minister Trudeau announced multiculturalism as an official government policy. On the 50th anniversary of the announcement, Canadian Geographic is publishing five essays that explore the theme. The series forms part of Commemorate Canada, a Canadian Heritage program to highlight significant Canadian anniversaries. It gives Canadian Geographic a chance to look at these points of history with a sometimes celebratory, sometimes critical, eye.

Canada’s policy of multiculturalism has kept the country’s intellectuals busy for years. Books and articles have been published asking if it brings people with diverse origins together or drives them apart. Debates have been held as to whether it reinforces or dilutes Canada’s linguistic duality. Philosophers have tried to pinpoint where the notion of multicultural accommodation reaches its limits in a liberal society. No one has run out of things to say.

For ordinary Canadians, however, multiculturalism has tended to be less controversial. Opinions consistently have been more positive than negative. By 2002, three in four Canadians approved of the federal policy of multiculturalism, compared to only 15 per cent who disapproved. In that same year, a large majority of Canadians believed the policy led to greater understanding between different groups in the country, while only a minority thought it produced greater conflict, or risked eroding Canadian identity or culture.

Even more remarkable than the general approval of multiculturalism as a policy is the extent to which we have incorporated it as a part of our own sense of national identity. When asked in regular surveys conducted over a 30-year period, from 1985 to 2015, no fewer than seven in 10 Canadians said that multiculturalism was important to the Canadian identity. The figure in 2015 reached 87 per cent.

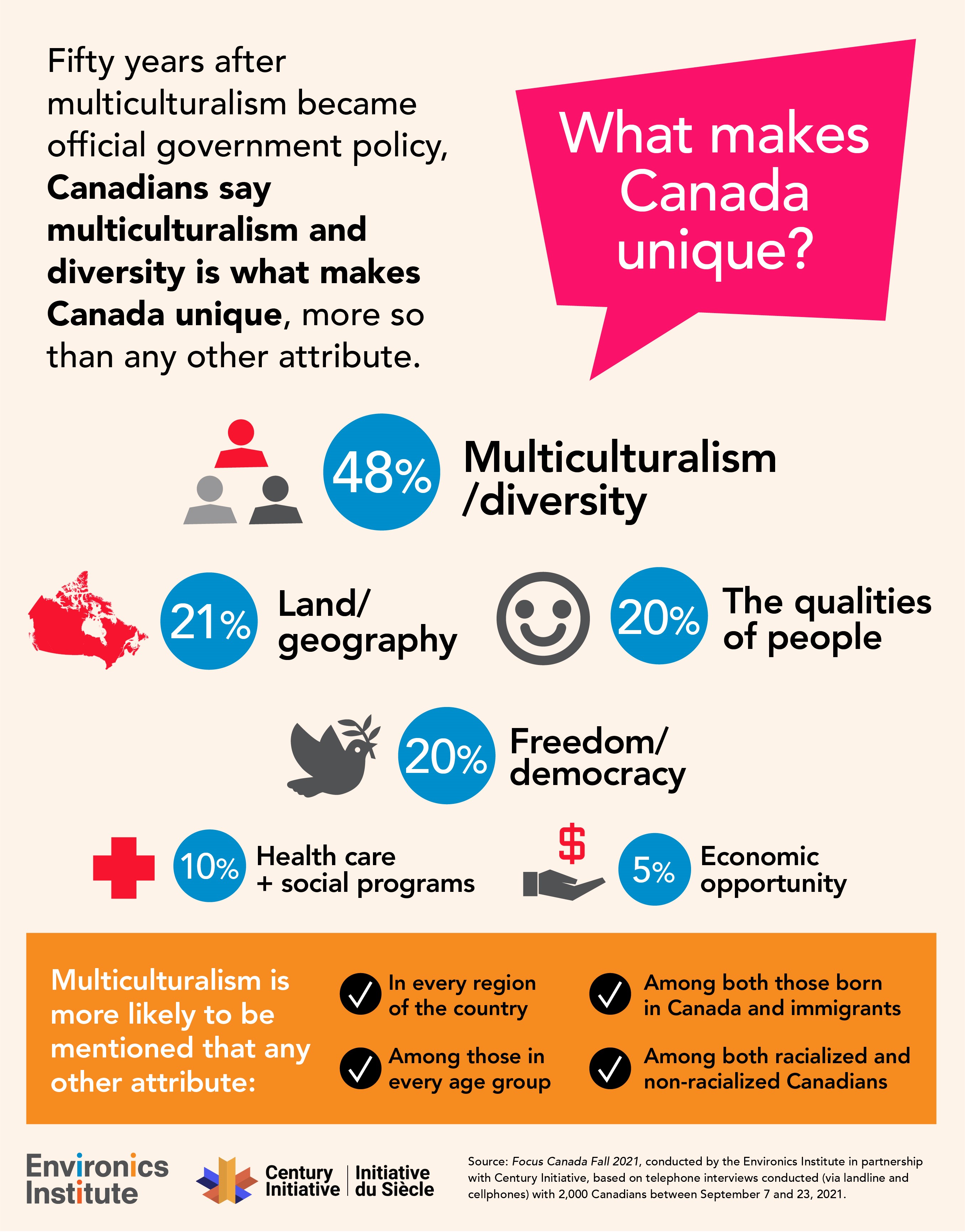

It is not that Canadians feel obligated to respond positively to the concept when pollsters put it in front of them. They also are more likely to spontaneously mention multiculturalism than any other policy or value in open-ended questions — ones that allow them to respond in their own words. In a new survey just completed in September 2021, for instance, Canadians were more likely to mention multiculturalism than any other idea that came to mind when describing, in their own words, what makes Canada unique. Thirty-one per cent mentioned multiculturalism specifically, more than two and a half times as many as mentioned the next most popular items (the land, and freedom and democracy — each mentioned by 12 percent). Forty per cent mentioned either multiculturalism, the acceptance of immigrants and refugees, or the country’s inclusiveness. Moose, mountains and Mounties have been displaced in our imaginations by the pedestrian concept “multiculturalism.” A concept a federal bureaucrat invented in 1971. Only in Canada.

Views about multiculturalism do not exist in a vacuum — they are connected to opinions on a much wider range of issues related to the country’s diversity. In the five decades since the multiculturalism policy was adopted, these opinions have undergone a remarkable transformation. In late 1970s and early 1980s, Canadians were twice as likely to agree than to disagree with the proposition that there was too much immigration to this country. Today, it is precisely the opposite: twice as many Canadians disagree as agree. A generation ago, a majority was skeptical about the claim that it is more difficult for non-white people to be successful in this country than it is for those who are white; today, a majority accepts this as a problem we need to address.

Certainly, one reason Canadians have become more open to immigration is the understanding of its link to economic growth. Four in five Canadians, for instance, think that overall, immigration has a positive impact on our economy. But it would be wrong to think that it all comes down to an instrumental calculus. When supporters of immigration are asked to say why they think new arrivals make our country a better place to live, their top answer is not their contribution to the economy, but the fact that new immigrants add to the country’s multicultural fabric. It makes Canada a more interesting and vibrant place to live.

Multiculturalism is many things. It has been a policy, a piece of legislation, a clause in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and a government department. But for most Canadians, it is also a common sense, everyday part of their understanding of themselves and their country. In this way, it resembles the Canada Health Act, which is cherished not just as a law underpinning the health care system, but as a symbol of what it is we aspire to as a society.

Experts will continue to debate the successes and challenges of government policies. Concerns most recently have been expressed about the under-use of the skills that immigrants bring with them, about the tenuous situation of temporary foreign workers, and about the presence of Islamophobia and other forms of intolerance. These and other issues must be addressed in turn. But they can be addressed on a foundation of solid public support for the country’s multicultural character. Whether and how we can do better is always a conversation worth having. But there can be little doubt that Canadians have been and remain committed to the goals we had set for ourselves though the policy of multiculturalism many decades ago.

No political party or parliamentarian elected to our House of Commons in the recent September 2021 election, including the dozens of those born abroad, would even dream of rejecting the principles behind Canada’s unique contribution to the vocabulary of pluralism. In what other country would that be true?

Michael Adams is the founder and president of the Environics Institute for Survey Research, a non-profit and non-partisan entity whose mission is to sponsor relevant and original public opinion and social research on issues of public policy and social change. He is also the author of seven books, and a regular contributor of published commentary on Canadian values and social trends. His most recent book, published in 2017, is Could it Happen Here? Canada in the Age of Trump and Brexit.

Like what you're reading? With our bi-monthly e-newsletter, you can receive even more with the latest details on current projects, news, and events at the institute.

Subscribe